“I don’t do frilly,” says curator Diane Schaub. We are standing under the shade of an old magnolia in the English garden, one of three smaller gardens within Central Park’s six-acre Conservatory Garden near the northeast corner of the park.Here are 10 of her perfect color combinations for fall garden beds:

Photography by Marie Viljoen for Gardenista.

Burgundy and Green

![lancelot2-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: “This is as frilly as I go,” she clarifies, indicating a velvet-leafed plant with burgundy leaves, beside the bluestone path. The plant in question is a

Solenostemon (formerly classified as Coleus) and the cultivar is ‘Lancelot.’

![lancelot1-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above:

Solenostemon ‘Lancelot’ (paired with

Salvia ‘Paul’) belongs to a crew of leafy annuals whose impact is felt dramatically in this garden, where the seasonal spectacle owes a great deal to plants whose interest lies in their foliage.

Purple, Yellow, and Blue

![purpleprince-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: If you thought leaves were boring, think again.

Solenostemon ‘Purple Prince’, black-leafed

Dahlia ‘Mystic Illusion’, and

Salvia farinacea ‘Victoria Blue’.

Purple and Red

![redhead-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: Elephant-eared

Colocasia esculenta ‘Black Magic’,

Solenostemon ‘Redhead’, and

Agastache cana ‘Heather Queen’.

Schaub, who earned a diploma from the New York Botanical Garden’s School of Professional Horticulture, has been the Conservatory Garden’s curator for 20 years. And while she does not do frilly, she does do color and texture, breathtakingly well. She has a painter’s eye for composition and an architect’s instinct for structural detail.

Purple and Lilac

![pennisetum-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: A bed of

Pennisetum setaceum ‘Rubrum’,

Salvia x ‘Indigo Spires’, the leafy and lilac-striped

Strobilanthes dyeranus, and elephant-eared

Colocasia esculenta ‘Blue Hawaii’. The latter “makes the whole composition work,” says Schaub. Dark purple

Pennisetum ‘Vertigo’ is in the background.

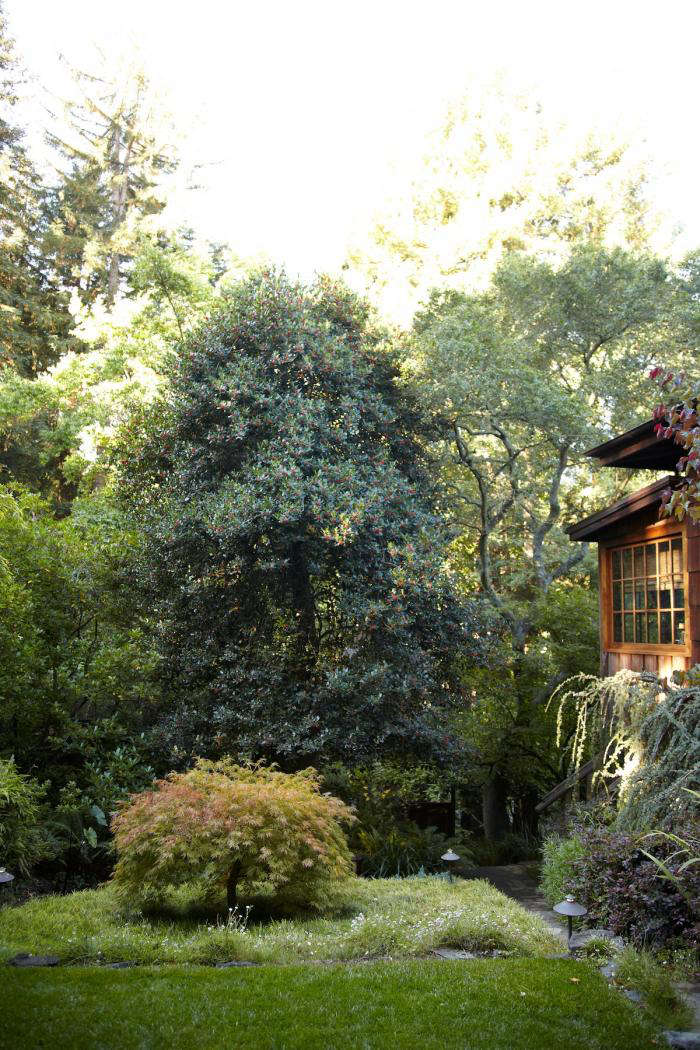

![secret garden-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: The English Garden is arranged in beds radiating from a central pond overhung by the largest crabapple tree in Central Park, leaves now turning yellow. Designed by Betty Sprout and opened in 1937, by the 1970s this part of the park was considered one of the most dangerous places in New York City. In 1980, the Central Park Conservancy was formed in response to the neglect the park had suffered in the previous two decades. Its new director, Elizabeth Rogers, earmarked the Conservatory Gardens for renovation.

![hedges-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: Lynden Miller, now a legendary public garden designer, but then a painter and home gardener, was asked by Rogers to revisit the original plans. She redesigned the perennial beds. Miller was also vehement in her advocacy for a maintenance budget, something many public plantings sorely and visibly lack. Gardens are work, and this seasonal showcase is not low maintenance. The Conservatory Garden’s staff of six, with the help of 20 regular volunteers, is kept busy.

![berberisball1-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: Within the backbone of green hedging, shrubs, and perennials, the beds are punctuated occasionally by Miller’s trademark:

Berberis thunbergii balls. The manicured shape helps prevent the invasive shrub from spreading, by preventing fruit-set. The low evergreen hedges (

Ilex crenata,

Euonymous ‘Manhattan’ and

Berberis julianae) allow intimate niches within beds, so that “you arrive in a different and lovely place” every few paces, explained Schaub.

![arcs-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: Annuals dominate the interior beds, while the outer arcs are filled with perennials and shrubs. Every winter Schaub (also a fine art major at City College of New York) sketches by hand her new plans for spring and summer schemes. Orders for thousands of summer annuals and perennials must be placed by October of the previous year for May planting, so growers on Long Island have time to propagate enough stock. On planting day, volunteers line up early to carry flats of plants to their assigned positions. Each bed has its own map.

Red, Yellow, and Silver

![redzinnia-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

cAbove: The red

Zinnia ‘Benary’s Giant Deep Red’ pops out in a border with feathery gray

Centaurea gymnocarpa, lime green

Zinnia elegans ‘Envy’, and the chocolate-y backdrop of

Pennisetum ‘Vertigo’. In the background, yellow

Rudbeckia laciniata and the silver-leafed sunflowers,

Helianthus argophyllus, draw the visitor farther in.

Orange, Yellow, and Lime

![arctotis-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: A lesson in warmth. From front to back: a yellow variegated Lantana,

Arctotis x ‘Flame’,

Agastache mexicana ‘Acapulco Orange’, with tall

Asclepias curassavica ‘Silky Gold’ behind it, a sprawling sweet potato—

Ipomea batata ‘Sweet Caroline Bronze’, and a mass of lime green

Solenostemon ‘Dappled Apple’ in the background.

Pink, Fuchsia, and Lime

![cleome-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: “Pinks are hard,” says Schaub, discussing color pairing: “Some are bluish; some are orange. You can really err.” Here, the blue pinks are played off against two stalwarts that are used often in these beds: glaucus

Melianthus major, in the foreground, and fuchsia-striped

Perilla ‘Magilla’. Tall pink

Cleome ‘Clio’ brushes against

Salvia ‘Waverly’ with silvery cardoon (

Cynara cardunculus), hot pink

Gomphrena ‘Fireworks’, and lime

Ipomoea batata ‘Dwarf Marguerite’, which keeps the composition fresh.

Pale Pink and Sky Blue

![chasmanthium-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: Pale pink

Verbena ‘Lavender Cascade’ does just that over the flagstones, under the tresses of sea oats (

Chasmanthium latifolium) and the sky blue confetti of

Browallia americana.

Yellow and Blue

![melampodium-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: The small yellow flowers of

Melampodium ‘Son of Garth’ cluster around the intense blue of

Salvia x ‘Indigo Spires’.

Solenostemon “˜Lancelot’ and sweet potato (

Ipomoea batata ‘Dwarf Marguerite’, again) create volume.

Yellow, Lime, and Purple

![black-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: Below a hedge of clipped

Ilex crenata Halloween-ready

Dahlia ‘Mystic Illusion’ anchors a corner where purple

Alternanthera dentata ‘Rubiginosa’ sprawls between supporting mounds of lime

Solenostemon ‘Dappled Apple’ and a variegated and stiff-leafed

Plectranthus forsteri ‘Green on Green’. The spires of

Salvia guaranitica ‘Royal Purple’ loosen the composition in the background.

![hummer2-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: Ruby-throated hummingbirds visit the nectaries of

Cuphea platycentra ‘David Verity’ as well as a collection of sweetly tubular Salvias, Agastaches, and Leonotis, which must put the English Garden firmly on the hummingbirds’ migratory map.

![chrysalis-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: No pesticides are used in this garden, though “I do take a hose to aphids,” says the curator, grimly. A variety of milkweeds lures monarch butterflies to the garden. Their larvae feed on the bitter leaves of the genus Asclepias. On a recent visit, the pale green chrysalis of a monarch hung suspended in gold thread from a blade of purple

Pennisetum setaceum ‘Rubrum’;

it’s the most appropriate garden art I have ever seen.

![english garden1-marie-viljoen-gardenista]()

Above: If you are within reach of New York City, visit this early fall iteration of the English garden before the end of October, when all the summer annuals will be removed, and tens of thousands of spring bulbs will be planted for next spring.

And if you are a little late, walk north to the French-style garden where the Korean chrysanthemums on display might just blow your mind.

But that is another story.

For more gardens to admire, journey to Scampston Hall by Dutch Master Piet Oudolf and Cape Town for A Study in Green with Franchesca Watson. You can also spend an entire afternoon exploring all our Garden Visits.

Above: When you co-opt the table lamp, normally reserved for living rooms and bedrooms, for use in kitchen, the result is altogether charming. Photograph by Victoria Pearson, from Kitchen of the Week: A Photographer’s Flexible Studio Kitchen in Ojai Valley.

Above: When you co-opt the table lamp, normally reserved for living rooms and bedrooms, for use in kitchen, the result is altogether charming. Photograph by Victoria Pearson, from Kitchen of the Week: A Photographer’s Flexible Studio Kitchen in Ojai Valley.

Above: Elevate the humble fruit bowl (literally) by using footed bowls instead. Photograph by Laure Joliet, from Steal This Look: A Los Angeles Architect’s Low Key but Elegant Kitchen.

Above: Elevate the humble fruit bowl (literally) by using footed bowls instead. Photograph by Laure Joliet, from Steal This Look: A Los Angeles Architect’s Low Key but Elegant Kitchen.

Above: Utilitarian and attractive, invest in a durable broom crafted from natural materials. Photograph by Alexandra Ribar, from Hygge in Ohio: An Architect’s Scandi-Inspired Off-the-Grid Hut.

Above: Utilitarian and attractive, invest in a durable broom crafted from natural materials. Photograph by Alexandra Ribar, from Hygge in Ohio: An Architect’s Scandi-Inspired Off-the-Grid Hut.

Above: Art has a place in the kitchen, too! Here, a beautiful landscape painting gets place of honor. Photograph by Alexis Hamilton for British Standard, from 16 Favorite Solid Marble Kitchen Backsplashes, for Maximum Drama. (For more examples of art in the kitchen, see The New Art Gallery: 12 Favorite Kitchens with Paintings on Display.)

Above: Art has a place in the kitchen, too! Here, a beautiful landscape painting gets place of honor. Photograph by Alexis Hamilton for British Standard, from 16 Favorite Solid Marble Kitchen Backsplashes, for Maximum Drama. (For more examples of art in the kitchen, see The New Art Gallery: 12 Favorite Kitchens with Paintings on Display.)

Above: Saturated salvia shines in autumn’s low-angled light. At left, Salvia curviflora at Gravetye, with the dahlia ‘Magenta Star’.

Above: Saturated salvia shines in autumn’s low-angled light. At left, Salvia curviflora at Gravetye, with the dahlia ‘Magenta Star’.

Above: Tall and stately Salvia curviflora with Verbena macdougalii ’Lavender Spires’ at Gravetye.

Above: Tall and stately Salvia curviflora with Verbena macdougalii ’Lavender Spires’ at Gravetye.

Above: With Salvia curviflora in the double border at Gravetye, fuzzy purple and white Salvia leucantha blooms at right.

Above: With Salvia curviflora in the double border at Gravetye, fuzzy purple and white Salvia leucantha blooms at right.

Above: Salvia leucantha

Above: Salvia leucantha

Above: Gravetye senior gardener Stuart Lambert carries cuts of the Brazilian native Salvia confertiflora to the house florists.

Above: Gravetye senior gardener Stuart Lambert carries cuts of the Brazilian native Salvia confertiflora to the house florists.

Above: Salvia ‘Phyllis’ Fancy’ at Gravetye with Diascia personata, both flowering into late October.

Above: Salvia ‘Phyllis’ Fancy’ at Gravetye with Diascia personata, both flowering into late October.

Above: Salvia involucrata ‘Bethellili’ at Gravetye.

Above: Salvia involucrata ‘Bethellili’ at Gravetye.

Above: Salvia involucrata ‘Bethellili’ at Gravetye.

Above: Salvia involucrata ‘Bethellili’ at Gravetye.

Above: Propagate salvias from semi-ripe stems in late summer. These young plants at Gravteye were started from cuttings taken in late August. They will be held in 2-liter pots under glass over the winter.

Above: Propagate salvias from semi-ripe stems in late summer. These young plants at Gravteye were started from cuttings taken in late August. They will be held in 2-liter pots under glass over the winter.

Above: The coral Salvia ‘Ember’s Wish’ harmonizes with fall foliage at Dyson’s Nursery in Kent, England.

Above: The coral Salvia ‘Ember’s Wish’ harmonizes with fall foliage at Dyson’s Nursery in Kent, England.

Above: Salvia ‘Love and Wishes’ at the Great Comp Garden in Kent, England. With burgundy calyces and stems, this salvia is a great choice for a pot or planter given its tidy habit and long-flowering period from June to November.

Above: Salvia ‘Love and Wishes’ at the Great Comp Garden in Kent, England. With burgundy calyces and stems, this salvia is a great choice for a pot or planter given its tidy habit and long-flowering period from June to November.

Above: For a tutorial on how to use leaves as mulch, see

Above: For a tutorial on how to use leaves as mulch, see  Above: In your garden, add mulch around plantings, but certain plants, such as garlic, need full coverage. “Garlic is typically mulched heavily with leaves or other materials, and left to go dormant through the winter before resuming growth in the spring,” explains Kenneth. The mulch minimizes frost heave (which forces the garlic out of the ground prematurely). See our

Above: In your garden, add mulch around plantings, but certain plants, such as garlic, need full coverage. “Garlic is typically mulched heavily with leaves or other materials, and left to go dormant through the winter before resuming growth in the spring,” explains Kenneth. The mulch minimizes frost heave (which forces the garlic out of the ground prematurely). See our  Above: Snowdrops enjoy the naturally dampish conditions of a woodland floor; adding leaf compost (aka “leaf mold”) makes them feel at home. See

Above: Snowdrops enjoy the naturally dampish conditions of a woodland floor; adding leaf compost (aka “leaf mold”) makes them feel at home. See

Above: The

Above: The  Above: A

Above: A  Above: The

Above: The  Above: Handmade in Sweden by Korbo, a 16-liter

Above: Handmade in Sweden by Korbo, a 16-liter  Above: The

Above: The

Above: This

Above: This  A

A

Above: Williams-Sonoma’s

Above: Williams-Sonoma’s

Above: The key to a chic French-inspired room? Nothing perfect, nothing rigid. Instead place a desk at an angle and let books lean any which way, as in this nook from a Paris apartment in

Above: The key to a chic French-inspired room? Nothing perfect, nothing rigid. Instead place a desk at an angle and let books lean any which way, as in this nook from a Paris apartment in  Above: Layer in floppy pillows, throws, and bedrolls for a rumpled-refined look. Julie found a great source for these soft elements in

Above: Layer in floppy pillows, throws, and bedrolls for a rumpled-refined look. Julie found a great source for these soft elements in  Above: One of our favorites? Manufacture de Digoin, the oldest pottery studio in the Loire Valley. See more French go-tos in

Above: One of our favorites? Manufacture de Digoin, the oldest pottery studio in the Loire Valley. See more French go-tos in  Above: You can never go wrong by adding a few vintage finds. Here, small vintage photographs, sourced at a flea market, add personality to a bathroom. Photograph by Nomades, courtesy of Le Barn, from

Above: You can never go wrong by adding a few vintage finds. Here, small vintage photographs, sourced at a flea market, add personality to a bathroom. Photograph by Nomades, courtesy of Le Barn, from

Above: Photograph by Marla Aufmuth for Gardenista, from

Above: Photograph by Marla Aufmuth for Gardenista, from  Above: A sampling of figs grown in the orchard of the University of California at Davis. Photograph by Marla Aufmuth for Gardenista, from

Above: A sampling of figs grown in the orchard of the University of California at Davis. Photograph by Marla Aufmuth for Gardenista, from  Above: Potted fig trees won’t grow as tall or wide as those planted in the ground. A 3-gallon pot of

Above: Potted fig trees won’t grow as tall or wide as those planted in the ground. A 3-gallon pot of  Above: The

Above: The Above: Photograph by Marie Viljoen, from

Above: Photograph by Marie Viljoen, from  Above: Let’s start with the Rolls Royce of fire pits, shall we? Made in the USA from corten steel, the beautifully sculptural

Above: Let’s start with the Rolls Royce of fire pits, shall we? Made in the USA from corten steel, the beautifully sculptural  Above: This elegant

Above: This elegant  Above: Looking for a fully portable solution? Try the stainless steel

Above: Looking for a fully portable solution? Try the stainless steel  Above: We love the rice bowl proportions of the cast iron

Above: We love the rice bowl proportions of the cast iron  Above: Loll Designs’

Above: Loll Designs’  Above: The

Above: The  Above: The top-rated

Above: The top-rated  Above: The

Above: The  Above: The

Above: The  Above: The streamlined

Above: The streamlined

Above: A red clay-tiled roof on a minimalist long house. Photograph by

Above: A red clay-tiled roof on a minimalist long house. Photograph by

Above: The clay roof tiles of this guesthouse are more than a hundred years old. Photograph courtesy of Riverside House, from

Above: The clay roof tiles of this guesthouse are more than a hundred years old. Photograph courtesy of Riverside House, from

Above: Magnolia ‘Iolanthe’ has big blooms on a young tree. Photograph by

Above: Magnolia ‘Iolanthe’ has big blooms on a young tree. Photograph by  Above: A majestic live oak is a focal point in landscape architect Christine Ten Eyck’s garden in Austin, Texas. (See her garden in our book,

Above: A majestic live oak is a focal point in landscape architect Christine Ten Eyck’s garden in Austin, Texas. (See her garden in our book,  Above: A bright idea from Julie: beautiful botanical wallpaper from venerable textile house Schumacher with a Shaded Vault from Workstead (one of our favorite design studios) in the same pattern. See more of the collaboration between the two brands in

Above: A bright idea from Julie: beautiful botanical wallpaper from venerable textile house Schumacher with a Shaded Vault from Workstead (one of our favorite design studios) in the same pattern. See more of the collaboration between the two brands in  Above: There’s no such thing as too much greenery indoors—even when there’s a wall of glass windows and doors looking out onto a lush courtyard. See more of this verdant kitchen in

Above: There’s no such thing as too much greenery indoors—even when there’s a wall of glass windows and doors looking out onto a lush courtyard. See more of this verdant kitchen in  Above: In a minimalist-rustic cabin in France, a branch of foliage offers just the right amount of color. Photograph by Jean Hay de Slade, courtesy of Epure, from

Above: In a minimalist-rustic cabin in France, a branch of foliage offers just the right amount of color. Photograph by Jean Hay de Slade, courtesy of Epure, from  Above: See more in

Above: See more in  Above: See more in

Above: See more in  Above: A non-functioning fireplace in a small bedroom by designer Elizabeth Roberts. Photograph by

Above: A non-functioning fireplace in a small bedroom by designer Elizabeth Roberts. Photograph by

Above: For similar artwork, visit

Above: For similar artwork, visit

Above: From the carport and entrance, the house appears to be a modest single-level building, albeit one with major curb appeal.

Above: From the carport and entrance, the house appears to be a modest single-level building, albeit one with major curb appeal.

Above: To the left of the entrance grows a Corylus avellana ‘Contorta’ (Corkscrew Hazel); to the right, growing in a stone planter, is Jasminum officinale.

Above: To the left of the entrance grows a Corylus avellana ‘Contorta’ (Corkscrew Hazel); to the right, growing in a stone planter, is Jasminum officinale.

Above: And here’s what’s on the other side. “I love having visitors who have not been here before as their surprise as they come into the house is always fun,” Anna told

Above: And here’s what’s on the other side. “I love having visitors who have not been here before as their surprise as they come into the house is always fun,” Anna told  Above: The defining feature of the house is a conservatory that promotes indoor-outdoor living. More importantly, it’s designed for energy efficiency. The two-and-a half-story south-facing conservatory, “as you would expect from any greenhouse, can get very hot in the sun. In the [colder] seasons, this heat is captured by the thermal mass of the building and then re-radiated at night. In the summer months, the heat is used to create air movement using the ‘stack effect,’ that is hot air rising and drawing air into the thermal chimney.”

Above: The defining feature of the house is a conservatory that promotes indoor-outdoor living. More importantly, it’s designed for energy efficiency. The two-and-a half-story south-facing conservatory, “as you would expect from any greenhouse, can get very hot in the sun. In the [colder] seasons, this heat is captured by the thermal mass of the building and then re-radiated at night. In the summer months, the heat is used to create air movement using the ‘stack effect,’ that is hot air rising and drawing air into the thermal chimney.”

Above: “The lowest part of the garden is a little courtyard outside the underground bedrooms. The stone flooring runs through from inside to out to connect the house to the garden,” says Anna.

Above: “The lowest part of the garden is a little courtyard outside the underground bedrooms. The stone flooring runs through from inside to out to connect the house to the garden,” says Anna.

Above: Galvanized steel steps lead from the basement courtyard to the the lower lawn, which has a well beneath it. “This water is used to pump into the house to flush the toilets and water the plants,” says Anna. “The sundial sits in a semicircle of slate and thyme. Al’s joke is carved into the oak post on which it’s set. ‘Look at the thyme; it’s slate.’ “

Above: Galvanized steel steps lead from the basement courtyard to the the lower lawn, which has a well beneath it. “This water is used to pump into the house to flush the toilets and water the plants,” says Anna. “The sundial sits in a semicircle of slate and thyme. Al’s joke is carved into the oak post on which it’s set. ‘Look at the thyme; it’s slate.’ “

Above: “Sitting on the balcony inside the conservatory is like being on the deck of a ship, particularly when it’s crisp and cold outside but the sky is blue and the winter sun is warming,” Anna said in The Modern House.

Above: “Sitting on the balcony inside the conservatory is like being on the deck of a ship, particularly when it’s crisp and cold outside but the sky is blue and the winter sun is warming,” Anna said in The Modern House.

Above: A meadow roof, with Cydonia oblongs ‘Vranja’ (Quince tree) hanging over. “It was seeded with a wild flower mix on sub soil originally, but as the fertility has increased the species have changed. Oxeye daisy and grasses predominate after the first flush of narcissus and fritillaries. We have a lovely little window looking into this at ground level from our dining room. At the height of summer it has the view point of lying in a meadow.”

Above: A meadow roof, with Cydonia oblongs ‘Vranja’ (Quince tree) hanging over. “It was seeded with a wild flower mix on sub soil originally, but as the fertility has increased the species have changed. Oxeye daisy and grasses predominate after the first flush of narcissus and fritillaries. We have a lovely little window looking into this at ground level from our dining room. At the height of summer it has the view point of lying in a meadow.”

Above: While much of the garden was designed to encourage play and creativity, there are also ample areas for rest and contemplation, like this nook, what Anna calls their “gin and tonic sitting area.” It’s in the upper level, the largest part of the garden. Catmint and Geranium x oxonianum flank the steps up to this level. A sweet secret lies among the cobblestones here: “The children’s treasured go-cart bits rest in peace amongst the stones.”

Above: While much of the garden was designed to encourage play and creativity, there are also ample areas for rest and contemplation, like this nook, what Anna calls their “gin and tonic sitting area.” It’s in the upper level, the largest part of the garden. Catmint and Geranium x oxonianum flank the steps up to this level. A sweet secret lies among the cobblestones here: “The children’s treasured go-cart bits rest in peace amongst the stones.”

Above: “Two small ponds are connected by a small square bog garden. I like bog garden species so I wanted to have an area to plant them. To get into the house from here, you have to walk over the slate slabs which appear to be floating on the pond. The ponds were designed to be right outside the sitting room windows so that the light from the water reflects onto the ceiling of our sitting room, making it feel Mediterranean on a sunny day.”

Above: “Two small ponds are connected by a small square bog garden. I like bog garden species so I wanted to have an area to plant them. To get into the house from here, you have to walk over the slate slabs which appear to be floating on the pond. The ponds were designed to be right outside the sitting room windows so that the light from the water reflects onto the ceiling of our sitting room, making it feel Mediterranean on a sunny day.”

Above: “We were determined when we first worked on the site 20 years ago to be patient and wait a year before planting to get rid of pernicious weeds,” Anna told The Modern House. “Consequently, maintenance has not been hard. The plants are chosen to fill the spaces and therefore weeding isn’t onerous.”

Above: “We were determined when we first worked on the site 20 years ago to be patient and wait a year before planting to get rid of pernicious weeds,” Anna told The Modern House. “Consequently, maintenance has not been hard. The plants are chosen to fill the spaces and therefore weeding isn’t onerous.”

Above: “We have a raised bed area to grow cut flowers, vegetable, and salad crops.”

Above: “We have a raised bed area to grow cut flowers, vegetable, and salad crops.”

Above: “I do most of the gardening, but Al cuts the yew and box hedging,” shares Anna. “The lawn has a Eunoymus japonica ‘Ovatus Aureus’ which he has shaped into a life sized car! When it’s a bit overgrown, like in this picture, I think that it looks like it’s going fast!” Photograph courtesy of Anna and Allan Joyce.

Above: “I do most of the gardening, but Al cuts the yew and box hedging,” shares Anna. “The lawn has a Eunoymus japonica ‘Ovatus Aureus’ which he has shaped into a life sized car! When it’s a bit overgrown, like in this picture, I think that it looks like it’s going fast!” Photograph courtesy of Anna and Allan Joyce.

Above: “When Al first showed me the derelict walled garden site, I understood that there was potential. I never dreamed it would end up being so delightful.”

Above: “When Al first showed me the derelict walled garden site, I understood that there was potential. I never dreamed it would end up being so delightful.”

Above: An established pomegranate tree in Sarah Price’s award-winning garden. Photograph by Jim Powell for Gardenista, from

Above: An established pomegranate tree in Sarah Price’s award-winning garden. Photograph by Jim Powell for Gardenista, from  Above: Not only are pomegranates delicious, but they also have decorative appeal. Photograph by Sophia Moreno-Bunge for Gardenista, from

Above: Not only are pomegranates delicious, but they also have decorative appeal. Photograph by Sophia Moreno-Bunge for Gardenista, from  Above: A 3-gallon container of

Above: A 3-gallon container of  Above: Pomegranate seeds add sweetness, crunch, and color to this salad. Photograph by Aya Brackett for Remodelista, from

Above: Pomegranate seeds add sweetness, crunch, and color to this salad. Photograph by Aya Brackett for Remodelista, from  Above: Pomegranates can also be used for dying fabric. Photograph by Maura Ambrose/Folk Fibers, from

Above: Pomegranates can also be used for dying fabric. Photograph by Maura Ambrose/Folk Fibers, from

Above: One of the beautiful rooms featured in Lisa Przystup’s new book,

Above: One of the beautiful rooms featured in Lisa Przystup’s new book,  Above: One of our favorite farmhouse kitchens ever. Photograph by Dana Gallagher, styling by Hilary Robertson, from

Above: One of our favorite farmhouse kitchens ever. Photograph by Dana Gallagher, styling by Hilary Robertson, from  Above: A classic pre-war New York City apartment, expertly decorated. See it in

Above: A classic pre-war New York City apartment, expertly decorated. See it in  Above: A long and lean house Park Slope house gets a functional and bright kitchen in

Above: A long and lean house Park Slope house gets a functional and bright kitchen in  Above: This home is situated in the bustling historic district of Mérida, but step inside its doors, and you’re transported into a light and airy sanctuary. Photograph by

Above: This home is situated in the bustling historic district of Mérida, but step inside its doors, and you’re transported into a light and airy sanctuary. Photograph by  Above: Deeply cut, arrowhead leaves of Hedera helix ‘Tripod’.

Above: Deeply cut, arrowhead leaves of Hedera helix ‘Tripod’.

Above: Not all ivy is big and self-supporting; many are small, thriving on wire supports.

Above: Not all ivy is big and self-supporting; many are small, thriving on wire supports.

Above: Slightly resembling Boston ivy (which isn’t in the ivy family), Hedera helix ‘Carolina Crinkle’ is highly decorative, requiring support.

Above: Slightly resembling Boston ivy (which isn’t in the ivy family), Hedera helix ‘Carolina Crinkle’ is highly decorative, requiring support.

Above: Hedera helix ‘Tussie Mussie’ is similarly pointed and pedate-leaved, with pale green splashes.

Above: Hedera helix ‘Tussie Mussie’ is similarly pointed and pedate-leaved, with pale green splashes.

Above: Hedera helix ‘Golden Curl’ is both variegated and crinkly around the edges. Its chartreuse coloring benefits from good light.

Above: Hedera helix ‘Golden Curl’ is both variegated and crinkly around the edges. Its chartreuse coloring benefits from good light.

Above: Hedera algeriensis ‘Gloire de Marengo’.

Above: Hedera algeriensis ‘Gloire de Marengo’.

Above: A vigorous American variety from 1950, Hedera helix ‘Parsley Crested’ has edges that are mainly crimped. The leaves turn to copper in autumn.

Above: A vigorous American variety from 1950, Hedera helix ‘Parsley Crested’ has edges that are mainly crimped. The leaves turn to copper in autumn.

Above: Glossy leaves of Hedera maroccana ‘Spanish Canary’.

Above: Glossy leaves of Hedera maroccana ‘Spanish Canary’.

Above: Amorphous in shape and pattern, Hedera colchica ‘Sulphur Heart’ does resemble a yellow-green heart.

Above: Amorphous in shape and pattern, Hedera colchica ‘Sulphur Heart’ does resemble a yellow-green heart.

Above: Small, star-shaped Hedera helix ‘Smithii’, which makes a good indoor plant.

Above: Small, star-shaped Hedera helix ‘Smithii’, which makes a good indoor plant.

Above: Hedera pastuchovii ‘Ann Ala’.

Above: Hedera pastuchovii ‘Ann Ala’.

Above: Ivy thrives in soil that is rich in limestone or rubble. Shown here is Variegated Hedera helix ‘Saint Agnes’.

Above: Ivy thrives in soil that is rich in limestone or rubble. Shown here is Variegated Hedera helix ‘Saint Agnes’.